Terraced Field Farming Rituals and Customs of Hani Ethnic Minority in Honghe County, Honghe

The Terraced Field Farming Rituals and Customs of the Hani Ethnic Minority in Honghe County, Yunnan Province, are a vital part of the UNESCO-listed Honghe Hani Rice Terraces (inscribed in 2013 as a World Cultural Heritage). Rooted in a millennium-old symbiotic relationship between the Hani people and their mountainous environment, these rituals embody their ecological wisdom, spiritual beliefs, and agricultural expertise.

Geographical Context and Terraced Ecosystem

- Location: Centered in Honghe County (红河哈尼族彝族自治州红河县) and surrounding areas of Honghe Hani and Yi Autonomous Prefecture, Yunnan. The terraced fields stretch across mountain slopes at elevations between 140 meters and 2,000 meters, covering over 16,000 hectares.

- Ecological System: The Hani have developed a unique “four-element integration” system—forests, villages, terraced fields, and waterways—where mountain forests act as natural water catchments, spring-fed channels irrigate terraces, and villages are nestled between forests and fields, ensuring sustainable agriculture for generations.

Historical Origins and Cultural Significance

- Millennia of Tradition: Hani terrace farming dates back over 1,300 years, evolving from ancient nomadic practices into a sophisticated sedentary system. The rituals reflect their reverence for nature (“Ohma,” the supreme god of nature) and ancestors, as well as their understanding of hydrology, climate, and crop cycles.

- Spiritual Core: Farming is not merely a livelihood but a sacred act tied to cosmic order. Rituals maintain balance between humans, nature, and the spiritual world, ensuring fertility, water security, and harvest prosperity.

Key Farming Rituals and Customs

The rituals follow the agricultural calendar, with ceremonies marking each stage of the farming cycle:

1. Pre-Farming Preparations (December–February)

- Forest and Water Worship (祭林神 / 水神): Before plowing, elders perform rites at mountain forests (“Awo”) and water sources to honor the “Forest God” and “Water God,” ensuring clean water flow. Cutting trees or polluting water sources is strictly taboo.

- Field Boundary Blessing (祭田界): Farmers mark field edges with sacred bamboo or stone pillars, praying for protection against pests and erosion.

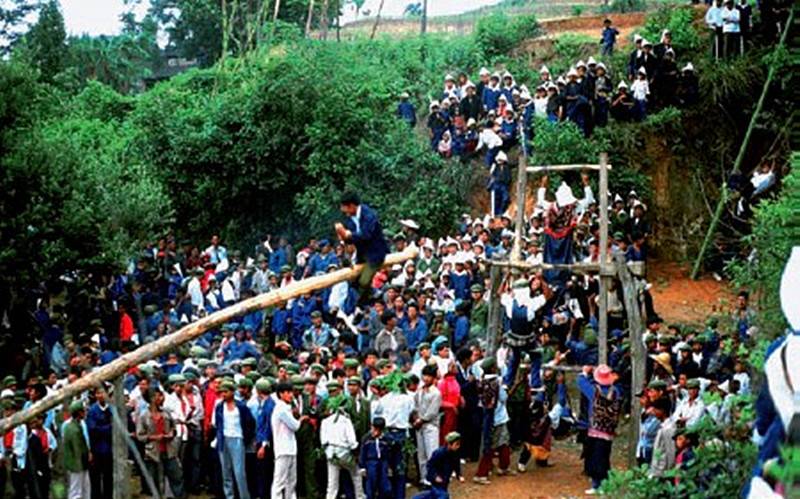

2. Plowing and Sowing (March–April)

- Opening the Plow (开犁节): The first plowing is led by the village chief, who offers rice wine, eggs, and incense to the field. Oxen are adorned with red cloth, symbolizing gratitude for their labor.

- Seedling Selection and Transplanting (育秧与栽秧)

- Seeds are chosen from the previous year’s best harvest, stored in ancestral altars. The “Opening the Rice Seedling Gate” (开秧门) ceremony begins with women singing 栽秧调 (transplanting songs) to bless the seedlings.

3. Field Management (May–August)

- Water Rituals (管水习俗): Water distribution is governed by a communal bamboo pipe system (“Magu”), with rituals to celebrate the arrival of spring water. The “Waterway Cleansing” (洗沟) ceremony involves collective maintenance of channels, preceded by offerings to the “Water Dragon God.”

- Weeding and Pest Control: Traditional songs (薅秧歌) are sung during weeding, believed to ward off pests and strengthen crops. Shamans may perform exorcism rituals for severe infestations.

4. Harvest and Thanksgivings (September–November)

- First-Fruit Offering (尝新节): The first rice harvest is presented to ancestors and the Kitchen God (“Gutang”) in home altars. Families share a ritual meal with new rice, symbolizing abundance.

- Field God Worship (祭田神): After harvest, farmers place offerings of rice cakes and wine at field corners, thanking the land and praying for next year’s yield. The “Closing the Terraces” (封田) ceremony marks the end of the farming cycle.

Folk Culture and Oral Traditions

- Epic Poems and Songs: The Hani Honey Tree Epic (《蜂蜜树》) and Terraced Field Chant (《梯田歌》) recount the origins of terrace farming and divine instructions for sustainable practices. Folk songs like Haiwa and Zhebi are performed during rituals, transmitting agricultural knowledge across generations.

- Crafts and Symbolism: Farming tools (wooden plows, bamboo water pipes) are decorated with ancestral motifs, while clothing features geometric patterns representing terraced slopes and rice plants.

- Community Harmony: Rituals emphasize collective responsibility—shared labor in terrace maintenance, equitable water distribution, and communal feasts reinforce social cohesion.

Protection and Inheritance

- World Heritage Status: The Honghe Hani Rice Terraces’ inclusion in the UNESCO list has highlighted the importance of preserving associated rituals and customs. Local governments have established cultural museums, supported elder-led workshops, and documented oral traditions.

- Ecotourism and Education: Rural homestays and guided farm tours allow visitors to participate in rituals like seedling gate ceremony and long-street feasts, generating income for villages while promoting cultural pride. Schools now teach Hani language and farming heritage to youth.

- Challenges: Urban migration and climate change pose threats to traditional practices. Efforts focus on training young farmers in ancestral techniques and integrating modern sustainability with ancient wisdom.

Cultural Legacy

The Hani terraced field rituals are a living testament to humanity’s ability to coexist harmoniously with nature. More than agricultural practices, they are a holistic philosophy—balancing productivity with ecological respect, and celebrating the interconnectedness of life, land, and the divine. As both a World Heritage site and a vibrant living culture, they continue to inspire global efforts in sustainable agriculture and cultural conservation.

http://www.ynich.cn/view-ml-11111-1165.html

Click to rate this post!

[Total: 0 Average: 0]