Bound Feet Women and Liuyi Village in Tonghai County, Yuxi

Chinese Name:玉溪市通海县秀山镇六一村

English Name: Liuyi Village of Xiushan Town in Tonghai County, Yuxi

Bound Feet Women In Liuyi Village Of Yunnan Province

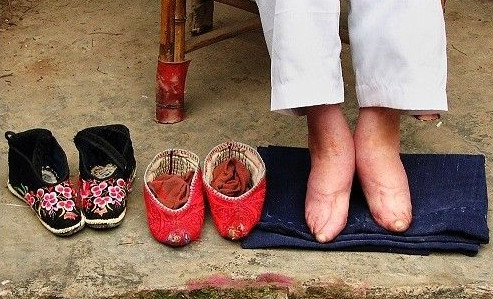

TONGHAI COUNTY, CHINA – APRIL 2: (CHINA OUT) 82-year-old bound feet woman Fu Jifen, makes ‘Three Cuns Golden Lotus’ shoes at Liuyi Village on April 2, 2007 in Tonghai County of Yunnan Province, China. ‘Three Cuns Golden Lotus’ is a term used to describe ancient Chinese women’s bound feet, in which three ‘cuns’ are about 3.39 inches.

Liuyi Village is known as the ‘Bound Feet Women Village,’ where over 100 female senior citizens with bound feet and over the age of 70 live. The Chinese custom of foot binding under the feudalization, which started during the Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907) , was discontinued in the early 20th century.

Liuyi Village of Tonghai County is home to around 300 elderly ladies who have bound feet since they were young. Particularly, people from outside have called the village “small-feet” village and “the last small-feet tribe of China”. Feet binding “Xiao Cun Jin Lian” or feet binding custom had been a feudal legacy and undesirable habit in the old times. But it was one of the criteria for judging whether or not a lady was beautiful.

Yunnan, the frontier area of China inhabited by more than a score of ethnic minorities, did not inherit such a custom before the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) when masses of Han Chinese began to migrate in–with the feet binding custom.

Tonghai, where the handicrafts industry and commerce were prosperous, was at that time one of the transportation hubs of Yunnan, and most ladies were confined to houses for weaving and housework. For many reasons, the feet binding had prevailed in the village.

Foot binding or Bound feet in China

Foot binding (simplified Chinese: ²ø×ã; literally “bound feet”) was a custom practiced on young girls and women for approximately one thousand years in China, beginning in the 10th century and ending in the first half of 20th century.

Foot-binding resulted in lifelong disabilities for most of its victims. As the practice waned in the early 20th century, “some girls’ feet were released after initial binding, leaving less severe deformities,” according to a study conducted by the University of California, San Francisco. However, some effects of foot-binding were permanent, especially if a girl’s arches or toes had been broken or other drastic measures taken in order to achieve the desired smallness. In the 1990s and early 2000s, some elderly (born until mid-1940s) Chinese women still suffered from disabilities related to bound feet.

Bound Feet: The story of China’s first modern divorce

The term “bound feet” conjures up a pretty powerful image for me. In China, it was considered beautiful and a must-have for women of high birth. At a young age, a girl’s toes were wrapped in bandages and bent under. It was a slow and painful process that involved breaking the bones until the foot was an arch several inches long, where women would only be able to walk on their heels and the knuckles of their toes.

As you might imagine, an operation like this made it difficult to walk, and almost certainly prevented one from being able to run. Even though it helped women achieve the ideal of tiny feet, it also arguably hindered their personal freedoms. A woman with bound feet wasn’t going to go anywhere fast, and they would naturally depend upon other people (usually their male relatives) for protection and their well-being.

As times changed, bound feet became a symbol of old China, of traditions and customs that were quickly dying out. In Bound Feet & Western Dress, author Pang-Mei Natasha Chang contrasts her own upbringing as a first generation Chinese-American with that of her great-aunt Chang Yu-I, a strong-minded woman who endured what is referred to as China’s first modern divorce.

[NextPage]

The Story

Natasha, or Pang-Mei as her family calls her, remembers growing up with stories about her family’s influence and wealth. In China, the Changs were a well-respected family, and even after their financial downfall Natasha’s great-uncles earned important positions as businessmen and politicians. As she pored over a textbook in a college course, Natasha came across an entry which listed her great-aunt Yu-I as being married, then divorced from Hsu Chih-Mo, a famous Chinese poet. It was difficult for Natasha to believe her elderly aunt as a major player in what must’ve been a fascinating story–a sign of the changing times in China and a defiance of social expectations.

She was so caught up with the idea that she began interviewing her aunt to get the entire story, and what she ended up with is a book about her family’s history from roughly 1900 to present times. The tale is told by alternating narrators, told from Natasha’s point of view as well as her great-aunt’s. The book begins with Yu-I’s childhood memories, her arranged marriage to Hsu Chih-Mo who barely gave her a moment’s thought, the birth of her children, their divorce and the career she later had as vice-president of the Shanghai Women’s Savings bank in the 1930’s. Also included is a great selection of family photos, of Yu-I as a young woman, her poet husband, children and even a shot of Natasha’s family.

What works

I’m fond of family histories, especially ones that cover entire generations. Natasha’s descriptions of growing up in Connecticut and the teasing she got as a result of her ethnic background definitely struck a chord in me. I too, had to deal with other kids making slanty-eyed faces at me, gabbling in fake Chinese and asking me inane questions like did I know karate or if Chinese people really ate dogs. (My answer, more often than not, was a sharp kick to the knee.)

Natasha struggled between two conflicting emotions–the desire to be proud of her family background and the desire to fit in with the other children. Even as she grew up and got a BA in Chinese studies from Harvard, Natasha still didn’t feel like she quite belonged, and didn’t feel like she had a special understanding of what it was to be Chinese or to be a member of venerable the Chang family.

I understand this odd feeling of limbo, the questionable feeling not-quite-belonging to either group. I’ve never been to China, and have spent all my life in the U.S. I understand only small amounts of Cantonese and don’t speak, read or write it. If I were to go to China, I’d stick out like a sore thumb despite being Chinese, and yet my ethnicity marks me out as different, not what most people think of when they think “American”. I’ve even been abused for using the term “Chinese-American”, as if to acknowledge that being Chinese was less than American or some sort of betrayal to my country . So I can definitely sympathize with Natasha’s struggle for a cultural identity. Parts of her story even made me wince, it was so familiar.

What I find a little harder to identify with–and this is only natural–is Yu-I’s part of the story. She did escape having her feet bound as a child, but that doesn’t make her some kind of feminist rebel. She did indeed have some ideas considered odd during that time. Yu-I wanted an education, not just for show but for real. But she was, in the early part of her life, very much bound by older traditions. Yu-I entered a loveless arranged marriage and stayed for as long as she could, being the dutiful wife and daughter-in-law. These two roles are more difficult than they seem, since “dutiful” often meant a great deal of self-sacrifice, where a daughter-in-law might be regarded as little more than a servant to her husband’s parents.

Even after she gained independence with a career of her own, Yu-I still is a little conservative in terms of what she considers proper behavior. She gently chides Natasha for what she sees as unfilial or borderline disrespectful behavior, and even offers to act as a match-maker for her great-niece–an especially surprising remark consider how her own arranged marriage turned out! Her ties to more traditional customs was in fact one of the irreconcilable differences between Yu-I and her husband, symbolized by the contrast of bound feet vs. western dress. Although her feet were unbound, a great deal about Yu-I was still old-fashioned in her husband’s eyes, while he was striving to be modern. Just as the ancient custom of foot-binding and western dress did not belong together, neither did Yu-I and Hsu Chih-Mo.

No, Yu-I is most certainly not one of those anachronistic enlightened heroines, and I like that because it’s more realistic. She was, after all, born in 1900. in a country where women are raised to believe in their lesser importance. It would be far more unusual if she’d thought exactly like her great-niece in terms of women’s liberation, etc. As it is, she’s refreshingly human and sometimes contradictory, since she herself pushed the bounds of many old customs but still has a lingering respect for them.

What Doesn’t Work

Probably the most confusing aspect of the book is its arrangement. Natasha and Yu-I’s respective stories aren’t organized into separate chapters, they’re simply separated by a small decorative symbol. When reading, I often failed to notice it and got extremely confused as to who was speaking at what time. After I got more into the story and became more familiar with each woman’s backgrounds, the identity of the narrator was a bit more obvious. I still think a more conspicuous separation of narrators would help, though.

My favorite part was Yu-I’s story, because I loved hearing about the traditions that seem quirky and old-fashioned to me now. Unfortunately, I’m not sure her character shone through quite as strongly as it could have. I get the feeling that Yu-I was a feisty person her time, not without prickles and stings, and I wish that personality came through a little stronger. I do like the feel of how the story is told, however…it is as if the reader was in Natasha’s shoes, sitting across the table from her great-aunt and listening to her story.

[NextPage]

Recommendations

I don’t expect writing on the level of Amy Tan’s wonderfully evocative detail, and that’s just as well because you don’t really get much of that here. I enjoyed bits of Chinese culture I didn’t know, like Yu-I’s explanation of the different types of jade, or her explanation of their names and each one’s meaning. Still, I’m afraid Tan’s novels–although they’re fiction–are still the benchmark for beautiful prose for me when it comes to writing about Chinese culture, the food, the clothes, the people…

I did like this book better than Falling Leaves: The True Story of an Unwanted Chinese Daughter mainly because I felt it was a little less soap opera-ish and maybe a bit more representative of what traditional family relationships were actually like. The theme of female empowerment is certainly familiar, and both narrators tackle this story from the woman’s viewpoint, always about what females had to deal with and overcome. While this is an admirable, interesting theme, it’s also been done before. What would interest me more is it a similar book could be written from a male perspective. While they weren’t as subservient as women back in those days, surely there must be some fascinating stories to tell, too.

I also think there could’ve been more explanation about things that might be unfamiliar to a western audience, like the arrangement of Chinese names (family name first, then personal name) or the concept of saving face and the obligations one had to older relatives. Still, I guess one could get a good grasp of these topics by reading from context even it lessens the impact somewhat.

Bound Feet & Western Dress was an interesting book, but not necessarily one I’d read more than once. There are quite a few books out on this subject, and while I found it interesting, it didn’t wow me so much that I have to keep a copy in my personal library. However, I’m glad Natasha Chang got to explore her family history, and I envy her a bit for being able to do so.

Source from: http://www.epinions.com/review/Bound_Feet__Western_Dress_by_Pang_Mei_Natasha_Chang/content_52060393092

[NextPage]

History by wikipedia.org

Multiple theories attempt to explain the origin of foot binding:[2] from the desire to emulate the naturally tiny feet of a favored concubine of a prince,[3][4] to a story of an empress who had club-like feet, which became viewed as a desirable fashion.[5] However, there is little strong textual evidence for the custom prior to the court of the Southern Tang dynasty in Nanjing, which celebrated the fame of its dancing girls, renowned for their tiny feet and beautiful bow shoes. What is clear is that foot binding was first practised among the elite and only in the wealthiest parts of China, which suggests that binding the feet of well-born girls represented their freedom from manual labor and, at the same time, the ability of their husbands to afford wives who did not need to work, who existed solely to serve their men and direct household servants while performing no labor themselves.[6][7][8] The economic and social attractions of such women may well have translated into sexual desirability among elite men.[9]

However, by the 17th century, Han Chinese girls, from the wealthiest to the poorest people, had their feet bound. It was less prevalent among poorer women or those that had to work for a living, especially in the fields. Some estimate that as many as 2 billion Chinese women were subjected to this practice, from the late 10th century until 1949, when foot binding was outlawed by the Communists. (Foot binding had also been banned by the Nationalists, but the Nationalists never had thorough political control over the entire country, and were unable to enforce this prohibition universally.)[1] According to the author of The Sex Life of the Foot and Shoe, 40-50% of Chinese women had bound feet in the 19th century. For the upper classes, the figure was almost 100%.[1] Generally speaking, footbinding was not as widespread in southern China as in the north. In contrast to the majority of other Han Chinese, the Hakka of southern China did not practice foot binding and had natural feet. Manchu women were forbidden to bind their feet by an edict from the Emperor after the Manchu started their rule of China in 1644. Many other non-Han ethnic groups continued to observe the custom, some of them practiced loose binding which did not break the bones of the arch and toes but simply narrowed the foot.

Binding the feet involved breaking the arch of the foot, which ultimately left a crevice approximately 5 cm (2 in) deep, which was considered most desirable. It took approximately two years for this process to achieve the desired effect; preferably a foot that measured 7–9 cm (3–3 1⁄2 in) from toe to heel.[10] While foot binding could lead to serious infections, possibly gangrene, and was generally painful for life, contrary to popular belief, many women with bound feet were able to walk, work in the fields, and climb to mountain homes from valleys below. As late as 2005, women with bound feet in one village in Yunnan Province formed an internationally known dancing troupe to perform for foreign tourists. In other areas, women in their 70s and 80s could be found working in the rice fields well into the 21st century. In the 19th and early 20th century, dancers with bound feet were very popular, as were circus performers who stood on prancing or running horses.

When foot-binding was popular and customary, women and their families and husbands took great pride in tiny feet that had achieved the desired lotus shape. This pride was reflected in the elegantly embroidered silk slippers and wrappings girls and women wore to cover their feet. Walking on bound feet necessitated bending the knees slightly and swaying to maintain the proper movement. This swaying walk became known as the Lotus Gait and was considered sexually exciting by men. Later, the Manchu women who were forbidden to bind their feet, and who were supposedly envious of the Lotus Gait, invented their own type of shoe that caused them to walk in a swaying manner. They wore ‘flower bowl’ shoes, on a high platform generally made of wood or with a small central pedestal. In fact, bound feet became an important differentiating marker between Manchu and Han women.

The practice of foot-binding continued into the 20th century, when both Chinese and Western missionaries called for reform; at this point, a true anti-foot-binding movement emerged. Educated Chinese began to realise that this aspect of their culture did not reflect well upon them in the eyes of foreigners; social Darwinists argued that it weakened the nation, since enfeebled women supposedly produced weak sons; and feminists attacked the practice because it caused women to suffer.[11] At the turn of the 20th century, well-born women such as Kwan Siew-Wah, a pioneer feminist, advocated for the end of foot-binding. Kwan herself refused the foot-binding imposed on her in childhood, so that she could grow normal feet.

There had been earlier but unsuccessful attempts to stop the practice of foot-binding, various emperors issuing unsuccessful edicts against it. The Empress Dowager Cixi (a Manchu) issued such an edict following the Boxer Rebellion in order to appease foreigners, but it was rescinded a short time later. In 1911, after the fall of the Qing Dynasty, the new Republic of China government banned foot binding. Women were told to unwrap their feet lest they be killed. Some women’s feet grew a 1–3 cm (1⁄2–1 in) after the unwrapping, though some found the new growth process extremely painful as well as emotionally and culturally devastating. Still, societies were founded to support the abolition of foot-binding, with contractual agreements made between families who would promise an infant son in marriage to an infant daughter who did not have bound feet. When the Communists took power in 1949, they were able to enforce a strict prohibition on foot-binding, including in isolated areas deep in the countryside where the Nationalist prohibition had been ignored. The prohibition on foot-binding remains in effect today.

In Taiwan, foot-binding was banned by the Japanese administration in 1915.

[NextPage]

Process of Bound Foot

The process was started before the arch of the foot had a chance to develop fully, usually between the ages of four and seven.[12][13][14][15] Binding usually started during the winter months so that the feet were numb, meaning the pain would not be as extreme.[16]

First, each foot would be soaked in a warm mixture of herbs and animal blood; this was intended to soften the foot and aid the binding. Then, the toenails were cut back as far as possible to prevent in-growth and subsequent infections, since the toes were to be pressed tightly into the sole of the foot. To prepare her for what was to come next, the girl’s feet were delicately massaged. Cotton bandages, 3 m long and 5 cm wide (10 ft×2 in), were prepared by soaking them in the blood and herb mixture. To enable the size of the feet to be reduced, the toes on each foot were curled under, then pressed with great force downwards and squeezed into the sole of the foot until the toes break. This was all carried out with no pain relief, causing the girl to experience severe pain. The broken toes were then held tightly against the sole of the foot. The foot was then drawn down straight with the leg and the arch forcibly broken. The actual binding of the feet was then begun. The bandages were repeatedly wound in a figure-eight movement, starting at the inside of the foot at the instep, then carried over the toes, under the foot, and round the heel, the freshly broken toes being pressed tightly into the sole of the foot. At each pass around the foot, the binding cloth was tightened, pulling the ball of the foot and the heel ever close together, causing the broken foot to fold at the arch, and pressing the toes underneath, this would cause the young girl excruciating pain. When the binding was completed, the end of the binding cloth was sewn tightly to prevent the girl from loosening it, and the girl was required to stand on her freshly broken and bound feet to further crush them into shape. As the wet bandages dried, they constricted, making the binding even tighter.

The girl’s broken feet required a great deal of care and attention, and they would be unbound regularly. Each time the feet were unbound, they were washed, the toes carefully checked for injury, and the nails carefully and meticulously trimmed. When unbound, the broken feet were also kneaded to soften them and make the joints and broken bones more flexible, and were soaked in a concoction that caused any necrotic flesh to fall off.[17] Immediately after this pedicure, the girl’s broken toes were folded back under and the feet were rebound. The bindings were pulled ever tighter each time, so that the process became more and more painful. Whilst unbound, the girl’s feet were often beaten, especially on the soles, to ensure that her feet remained broken and flexible. This unbinding and rebinding ritual was repeated as often as possible (for the rich at least once daily, for poor peasants two or three times a week), with fresh bindings. It was generally an elder female member of the girl’s family or a professional foot binder who carried out the initial breaking and ongoing binding of the feet. This was considered preferable to having the mother do it, as she might have been sympathetic to her daughter’s pain and less willing to keep the bindings tight. A professional foot binder would ignore the girl’s cries and would continue to bind her feet as tightly as possible. Professional foot binders would also tend to be more extreme in the initial breaking of the feet, sometimes breaking each of the toes in two or three separate places, and even completely dislocating the toes to allow them to be pressed under and bound more tightly. This would cause the girl to suffer from devastating foot pain, but her feet were more likely to achieve the 7 cm (3 in) ideal. The girl was not allowed to rest after her feet had been bound; however much pain she was suffering, she was required to walk on her broken and bound feet, so that her own body weight would help press and crush her feet into the desired shape.

The most common problem with bound feet was infection. Despite the amount of care taken in regularly trimming the toenails, they would often in-grow, becoming infected and causing injuries to the toes. Sometimes for this reason the girl’s toenails would be peeled back and removed altogether. The tightness of the binding meant that the circulation in the feet was faulty, and the circulation to the toes was almost cut off, so any injuries to the toes were unlikely to heal and were likely to gradually worsen and lead to infected toes and rotting flesh. If the infection in the feet and toes entered the bones, it could cause them to soften, which could result in toes dropping off—though this was seen as a positive, as the feet could then be bound even more tightly. Girls whose toes were more fleshy would sometimes have shards of glass or pieces of broken tiles inserted within the binding next to her feet and between her toes to cause injury and introduce infection deliberately. Disease inevitably followed infection, meaning that death from septic shock could result from foot-binding, but a surviving girl was more at risk for medical problems as she grew older. In the early part of the binding, many of the foot bones would remain broken, often for years. However, as the girl grew older, the bones would begin to heal, although even after the foot bones had healed they were prone to re-breaking repeatedly, especially when the girl was in her teens and her feet were still soft. Older women were more likely to break hips and other bones in falls, since they could not balance securely on their feet, and were less able to rise to their feet from a sitting position. Since the women in China weren’t able to walk properly anymore, most had to have servants do most of the cleaning, cooking, and caring of children and husband.

[NextPage]

Reception and appeal

Bound feet were once considered intensely erotic in Chinese culture.[19][20][21] Qing Dynasty sex manuals listed 48 different ways of playing with women’s bound feet.[1] Some men preferred never to see a woman’s bound feet, so they were always concealed within tiny “lotus shoes” and wrappings. Feng Xun is recorded as stating, “If you remove the shoes and bindings, the aesthetic feeling will be destroyed forever” — an indication that men understood that the symbolic erotic fantasy of bound feet did not correspond to its unpleasant physical reality, which was therefore to be kept hidden. For men, the primary erotic effect was a function of the lotus gait, the tiny steps and swaying walk of a woman whose feet had been bound. Women with such deformed feet avoided placing weight on the front of the foot and tended to walk predominantly on their heels. As a result, women who underwent foot-binding walked in a careful, cautious, and unsteady manner.[22] The very fact that the bound foot was concealed from men’s eyes was, in and of itself, sexually appealing. On the other hand, an uncovered foot would also give off a foul odor, as various saprobic microorganisms would colonize the unwashable folds.

Another attribute of a woman with bound feet was the limitations of her mobility and, therefore, her inability to take part in politics, social life, and the world at large. Bound feet rendered women dependent on their families, particularly their men, and, therefore, became an alluring symbol of chastity and male ownership, since a woman was largely restricted to her home and could not venture far without an escort or the help of watchful servants.

In literature and film

The bound foot has played a prominent part in many works of literature, both Chinese and non-Chinese. These depictions are sometimes based on observation or research and sometimes on rumor or supposition. This is only to be expected when a practice is so emotionally charged. Sometimes, as in the case of Pearl Buck’s The Good Earth, the accounts are relatively neutral.

Li Juzhen (1763–1830) wrote a satirical novel Jinghua yuan, translated as Flowers in the Mirror, which includes a visit to the mythical Kingdom of Women where men have to bear children, menstruate and bind their feet. In the novel Three Inch Golden Lotus the Chinese author Feng Jicai (b. 1942) presents a satirical picture of the movement to abolish the practice.

In the 1958 film The Inn Of The Sixth Happiness Ingrid Bergman portrays British missionary to China Gladys Aylward, who is assigned as a foreigner the task by a local Mandarin to unbind the feet of young women, an unpopular order that the civil government had failed to fulfill.

Ruthanne Lum McCunn wrote a biographical novel A Thousand Pieces of Gold (later adapted to a film), about Polly Bemis, a Chinese American pioneer woman. It describes her feet being bound, and later unbound when she needed to help her family with farm labour.